You know what your circadian rhythm does. It wakes you up at 05:30am every single day, even if it’s the weekend and you stayed up late last night and you need a little bit of extra sleep. It makes you hungry ten minutes before lunch, without fail, every single day. It ruins the first two days of your overseas trip by staunchly pushing you towards sleep because it’s 11:00PM back home, even though that’s the middle of the day and you’ve got holidaying to do. It makes it hard to go see your favorite band, because even through they’ve been playing for decades and are way older than you, for some reason their set finishes at midnight when you usually tap out at ten. You know what your circadian rhythm does, but how does it work?

Getting signals from the outside in…

The predominant signal for circadian rhythm in you, me and other surface-dwelling organisms is light. While you’re probably familiar with the cone and rod cells that facilitate vision, our circadian rhythms begin with a special non-visual photoreceptor named rather descriptively as “intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells” (or iPRGCs for brevity). Mammalian iPRGCs have a special photopigment called melanopsin, which is used to trigger a neural signal when activated by light with a wavelength of about 479nm (in humans), a pleasant cyan-blue. The amount of light required to trigger iPRGCs is quite variable across species: humans require around twenty minutes of morning sunlight, while rats and mice only require a short, dim pulse to set their clock.

In mammals, our “good morning” neural signal travels to a small, specialised brain region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which relays it to the pituitary gland. Other animals have directly photosensitive pituitaries. Both fish’s and lizard’s pituitaries extrude from the brain into a thin section of the skull in the centre of the top of the head. Here, photopigments like our very own melanopsin detect daylight and directly modulate pituitary activity, no suprachiasmatic nucleus required. Further complicating things is many fish seem to have circadian photoreceptors in their retina and brain that influence pituitary activity as well.

… Then all through the body…

Many of us know melatonin as a sleep hormone as it causes us (humans) to fall asleep at night. In nocturnal animals, however, melatonin is also elevated at night during their waking hours, meaning melatonin is more accurately darkness hormone than a sleep hormone. In mammals, melatonin is predominantly produced in the pituitary gland (and controlled by the aforementioned suprachiasmatic nucleus), but in birds, fish and reptiles melatonin is also produced in tissues like the retina, gut, bone marrow, platelets and skin. Similarly, melatonin receptors are concentrated in the pars tuberalis of the pituitary of mammals, but across the central nervous systems of birds, fish and reptiles. Here, melatonin signals to the cells and controls the core temperature rhythm and sleep propensity.

Glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol) are perhaps best known as “stress hormones”, but as is often the case in biology, things are not so simple as that. At the beginning of the active phase, whether it is the morning for diurnal animals or the evening for nocturnal ones, animals have a glucocorticoid pulse that signals the beginning of the active phase, whether that beginning is in the morning or the evening. Again, this is triggered by light activation (or the end of light activation for nocturnal species) of the pituitary as discussed earlier leading to the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH enters the bloodstream, where it travels to the adrenal glands and subsequently triggers the release of glucocorticoids. Glucocorticoids, such as the familiar cortisol and corticosterone, circulate via the bloodstream and enter cells, where they bind glucocorticoid receptors (GR) that target specific gene promoters called glucocorticoid response elements (GREs). GREs activate the positive arm of the circadian rhythm, among other processes.

… And into the cells

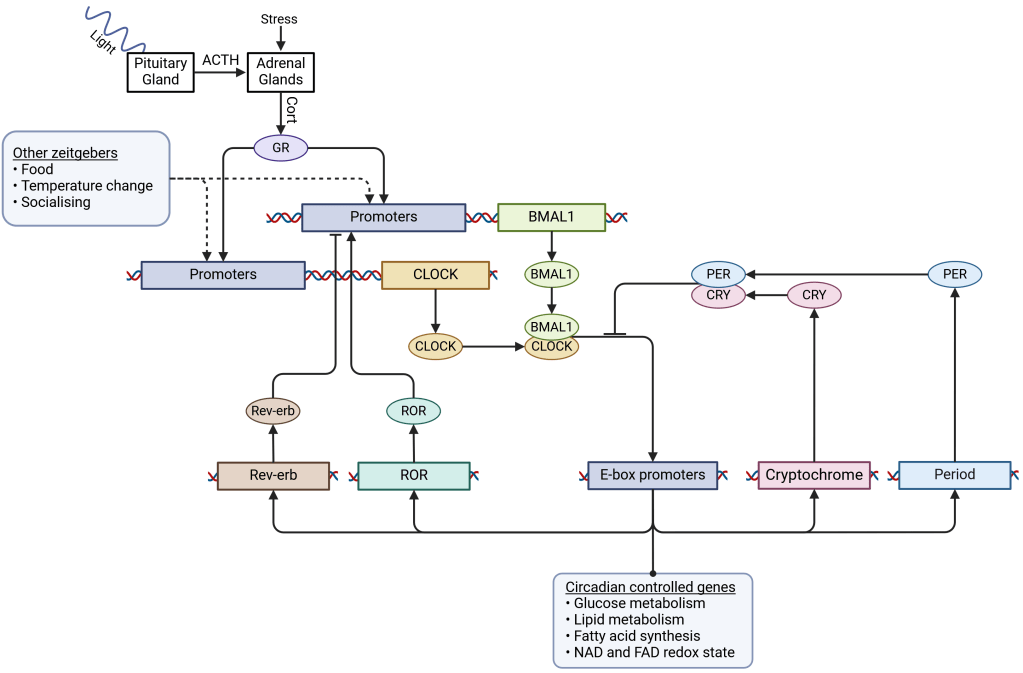

This section gets a little confusing, so I’ve included a graphic to follow as you read the text. Glucocorticoids activate the first half of a negative feedback loop in gene translation. Two genes called Circadian Locomoter Output Cycles Kaput (which someone really wanted to spell CLOCK) and Brain and Muscle ARNT-Like 1 (BMAL1) are transcribed and translated into transcription factors of the same names. CLOCK and BMAL1 transcription factors join to form a CLOCK-BMAL1 complex, which can bind to specialised gene promoters called E-boxes. E-box activation modulates a range of metabolic processes, changing how cells produce energy, and how they synthesise and degrade molecules like amino acids, nucleotides and nucleosides. Most notably for our circadian rhythm, E-boxes activate two other transcription factors: Period (PER) and Cryptochrome (CRY) which form a complex that physically cleaves CLOCK-BMAL1 from the DNA, reversing the activity caused by E-box promoters and signaling the end of the active phase. An additional feedback loop occurs through Rev-Erb and RAR-related orphan receptor (ROR) which competitively inhibit and enhance BMAL1 respectively. These proteins are expressed differently between biological tissues, giving tissue-specific enhancements to cyclic BMAL1 expression.

More than just light

While light is the one zeitgeber to rule them all, many tissues operate their clocks independently. The consumption of food is perhaps the most prominent secondary zeitgeber, modulating timekeeping (in mammals) in the liver, pancreas, small intestine, colon, muscle and adipose cells. The microbiome inside the gut also has a circadian rhythm, likely based to some extent on feeding routines. Complications arise in these tissues when highly palatable foods are readily available, like the chocolates sitting in your fridge. Such foods prompt eating at strange hours, leading to mixed signals from the master circadian clock and food consumption and subsequently lower peaks and higher troughs in the normally sinusoidal patterns of circadian transcription factors.

Modern life messes it all up

Modern life has zeitgebers in all the wrong places, and often not the right ones. Bright light of the right frequency, as discussed above, is necessary to trigger the glucocorticoid pulse in the morning, but life indoors under artificial light often prevents our sweet, sweet cortisol rush and inhibits the positive arm of the circadian rhythm. This in combination with artificial light at night inhibiting the negative arm means our comfortable lives indoors give us some very flat circadian rhythms.

Stress responses are activated by the same glucocorticoids as the positive arm of the circadian rhythm. This serves a useful evolutionary purpose, keeping individuals in stressful situations in their active phase while they’re under hot pursuit. Unfortunately, persistent stressors in the modern world like work pressures and doom scrolling limit our ability to transition to the inactive phase through the same mechanism.

This is by no means the limit of how life turns down the volume on our natural rhythms. Countless other facets of todays world lead our sensitive internal clocks astray:

- Social events

- Shift work

- Noise (traffic, air conditioner units)

- Late night snacks

- Psychoactive substances (caffeine, alcohol)

In conclusion

A suite of external and internal factors regulate circadian rhythms, which in turn regulate a suite of biological processes. These processes include things from sleep, to body temperature, to whether you burn stored fat or carbohydrates for energy. If our circadian rhythm gets lost because of our strangely lit and highly stimulated lives, so does our biology, potentially promulgating many health problems. Take care, look after your circadian rhythm and it will look after you.

Leave a comment